- Home

- Gert Ledig

The Stalin Front

The Stalin Front Read online

GERT LEDIG (1921–1999) was born in Leipzig and grew up in Vienna. At the age of eighteen he volunteered for the army and was wounded at the battle of Leningrad in 1942. He reworked his experiences during the war in this novel Die Stalinorgel (1955). Sent back home, he trained as a naval engineer and was caught in several air raids. The experience never left him and led to the writing of Vergeltung (Payback) (1956). The novel’s reissue in Germany in 1999 heralded a much publicized rediscovery of the author’s work there.

MICHAEL HOFMANN is a poet. He is the translator of nine books by Joseph Roth and was awarded the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Prize for translating The String of Pearls. He is also the translator of Wolfgang Koeppen’s two novels The Hothouse and A Sad Affair.

THE STALIN FRONT

A Novel of World War II

GERT LEDIG

Translated from the German and with an introduction by

MICHAEL HOFMANN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 2000 by Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main

Translation copyright © 2004 by Michael Hofmann

First published in Germany as Die Stalinorgel by Claassen Verlag, Hamburg, 1955

This translation first published in Great Britain by Granta Books, 2004

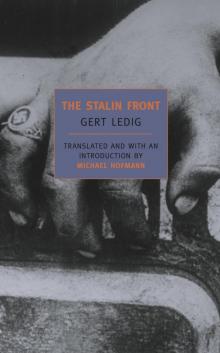

Cover photograph: Dead German soldier and tank, 1944; Keystone/Getty Images

Cover design: Katy Homans.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Ledig, Gert, 1921–

[Stalinorgel. English]

The Stalin front : a novel of World War II / by Gert Ledig ; translated and with an introduction by Michael Hofmann.

p. cm. — (New York Review Books classics)

ISBN 1-59017-164-0 (alk. paper)

1. World War, 1939-1945—Fiction. I. Hofmann, Michael,

1957 Aug. 25– II. Title. III. Series.

PT2623.E232S713 2004

833'.914—dc22

2005013038

ISBN 978-1-59017-815-7

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

CONTENTS

Biographical Notes

Title page

Copyright and More Information

Introduction

THE STALIN FRONT

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Epilogue

INTRODUCTION

Payback, translated by Shaun Whiteside and published in 2004, was Gert Ledig’s second novel. It is a brutally horrible account of seventy minutes – a ‘bomber’s hour’ – over an unnamed German city in 1944. As well as by the unstinting capacity to imagine and depict horror (and in particular a gruesome resourcefulness in chronicling some of the more extreme varieties of violent death), Ledig distinguishes himself by devising an impressively original vertical vision for the book, which literally makes a showing on every level: from the relative serenity of the American bomber crew, torn between vindictiveness and compassion (not that it matters much, they are one of four hundred); to the teenage ack-ack gunners on a tower four floors up; to a hapless old couple with nothing left to live for following the death of their son, looking at least to die together in their own home; to the lawlessness of street level, with bullying gangs of soldiers running rampant; to the underground shelter, finally, where desperate civilians sit out what may at any time turn out to be their last moments in darkness and fear. The two – downwardly – mobile things in a deliberately, stiflingly claustrophobic book are the American bombs, and Sergeant Strenehen, the American gunner, who accidentally follows them to their target area.

Ledig’s first book, originally published in 1955, the year before Payback, was Die Stalinorgel (literally, the Stalin organ). A Stalin organ is (I think) a reasonably current term of military slang for a multiple rocket launcher; the bunch of rockets does indeed look like organ pipes, or cigarettes in a packet; at the time, I would guess they were as destructive as anything conventional and terrestrial that had been invented. (The word isn’t used anywhere in the book, but the weapon’s effects are described in the Runner’s second scenario, on page 14). The setting here is outside Leningrad in the summer of 1942, some time after Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and prepared the way for some of the most tenaciously horrible fighting in the whole of the Second World War. (Ledig fought here, just as, incidentally, he had been a civilian later – it was in Munich – to witness the bombing of the cities.) Once again, the reader will sup full of horrors; but these things happened, are presently happening, and presumably will continue to happen; there is no point in pretending otherwise, and neither honour or security in putting them beyond the reach of literature. Not every writer wants, or is able to write about them, but in this bleak and daunting specialism, Gert Ledig is certainly a writer who should be read. In the brief spell of his life that he gave to writing, he wrote about nothing else. In an almost Faustian way, one might think he kept his side of the bargain. Each of his three books is a ‘war book’.

In the time since I first read Ledig, two years ago, I have revised my opinion of him as a writer. Nothing finds out a writer like translating him, and Ledig, I am glad to say, comes out of it, in my view, as someone of considerable skill and reach. It is easy to think of him – as the German critics have done, to some extent – as a necessary purveyor of unpleasantnesses, but he is better than that. He is a dramatic novelist, who works in scenes and writes clever dialogue. He organizes war into a plot, and drives its full force through what – among so much intentional mayhem and blind chance – come to seem relatively fine capillaries, like individual psychology and cause and effect. A whole chain of intrigue is set in motion by slight impairments of judgement and hairline reactions to events. The Stalin Front is a thoroughly worked out, plotted book. War, for all its random destructiveness, is proposed to us as a machine, and the novel is also a machine. There is the intricacy almost of farce in its operation. (Think about the episode near the end, say, where the Sergeant has to be killed, as it were for bureaucratic or accounting reasons, because he is already dead on paper.) It hits you with the Whitehall farce and the Imperial War Museum, both together. It is an unlikely thing in a book in which ranks are used in preference to names (and I have therefore capitalized them, to make them stand out a little better), but we actually come to understand a great deal about individual motivation of the different characters. In a way, the whole idea of ‘character’ in relation to war is preposterous – especially as much of the character shown is so petty or malignant – but on the other hand, it’s all there is, and it may make the difference between living and dying. Character, as the Greeks knew, is destiny. All this is used by Ledig to make not just a picture, but actually a moral vision of war, not least as something psychologically deforming.

The Stalin Front is, among other things, a sort of riposte to Ernst Jünger, whose 1920 book, Storm of Steel, glorified the violence of World War One, and asserted both the value of war and the triumph of the human spirit. The trench fighting (unexpected in the Second World War) and the military landscape both seem to me to hark back to World War One;

the syllable ‘stal’ appears in both titles; there is one explicit reference to Jünger’s book on page 82 (‘A black steel storm hung menacingly over the Front.’). Having, quite fortuitously, translated both books in the space of little over a year, it wasn’t just my fault that I sometimes didn’t know where I was! While Ledig’s account of warfare – most unlike Jünger’s – sticks rigorously and programmatically to its ‘low’, discreditable aspects, such things as suicide, murder, self-mutilation, desertion and dementia – it also, very occasionally, offers strikingly aestheticizing touches, much as Jünger does. ‘thin strokes of a barbed wire fence’ (page 59) is a phrase of Japanese pen-and-ink delicatesse with black and white; and one bizarre phrase on page 149, about ‘red and green pansy-coloured pearls’ (penseefarben – it’s quite as odd as that in German) must be a take-off of Jünger’s celebrated or notorious sense of colour. Ledig described The Stalin Front as ‘eine Kampfschrift’, which is the German word for pamphlet or polemic; he might have written it specifically against Jünger, who might have called his own book exactly the same thing – only in its literal sense of ‘fighting writing’.

Like Payback, The Stalin Front is a strikingly geometrical book. Where that had its vertical strata of activity, in keeping with the thrust of the bombing war, The Stalin Front sticks pretty much to one plane in its choice of terrain – the railway line, a few roads, woods and swamps, and above all the hill – but contrives a situation in which each side is surrounded. (It is characteristic of Ledig that he treats both sides equally; he is almost democratically impartial in his treatment.) Both the Major’s desperate band of Germans and Trupikov’s Russians are encircled. The pattern reminds me of the circles in a mandala, with each set in a preponderance of the other. Or perhaps of the Ugolino episode in Dante’s Inferno, where both Ugolino and his opponent, Archbishop Roger, are bitten fast into the other. Against that greater symmetry, there are numerous other instances of symmetry or parity of detail: the woundings and killings, the journeys, the glimmerings of another, civilian life, occasional italic inserts for flashbacks or hallucinations, down to quite tiny things like rings, diagrams, cigarettes and pieces of paper. This strongly symmetrical structuring allows each actor in the interdependent drama to function as a possible centre, the hero of his or her own story: the Runner, the Captain, the Major, Zostchenko, Sonia, Trupikov, the Sergeant. The contrast with, as it were, the standard ‘war story’, with its single sanctioned point of identification and single line of action, could not be stronger than with Ledig’s mobile sympathies and versatile changes of angle.

Perhaps the thing that for me clinches Ledig’s quality as a writer is what he does with nothing. (It’s like looking at the lower edge of religious or otherwise heroic Renaissance paintings, at the sampler of stray plants and insects one often finds.) One would have to concede, I think, that his writing about the extremities of life and action – say, pain, danger, cruelty – is persuasive, and that Ledig’s trademark way of registering insults to dead bodies is unforgettably macabre, but what is he like without such things? I would see it in a detail such as the moth he has fluttering around the lamp while the Cavalry Captain is being interrogated, or the spider’s web he feels in his face in the barn, shortly after. I would point to a sentence – a courtly, lacquered, Japanese sentence – like: ‘A beetle in shining armour dragged a blade of grass across the path’ (page 13), in the middle of all sorts of dread and drama. (Quite possibly, incidentally, another Jünger touch, for Jünger was a noted entomologist.) Or, in the same scene: ‘There was a field-kitchen installed on the edge of the forest. The co-driver was feeding fresh wood into the furnace. A few embers spilled out. The lid of the cauldron was open. The steam smelled of nothing in particular.’ (page 32) That ‘nothing in particular’ – a lesser writer would have given you God knows what – is actually a touch of greatness. It’s the same thing, I think, later on in the book, where Shalyeva, after her ordeal as a nurse, notices the softness of the grass; or where the Runner, after pages of the most brutal torture, and after picking up his teeth (the description ‘hard pieces of dirt with blood on them’ is unforgettable), is given this simple sentence: ‘He ran in the sun.’

When The Stalin Front first appeared in 1955, having been rejected by fifty publishers, it surprised pretty much everyone by being a considerable success. It sold many copies, and was translated into several other languages. Then it disappeared, its successors disappeared, and Ledig himself disappeared. For a variety of reasons, he wasn’t cut out for a literary career, and the divided Germany of the 1950s wasn’t perhaps the place to offer one to the likes of him either. By the time he died in 1999, he knew – ironically! – that there was a Ledig revival on the way, but he didn’t live to see any of his books in print again.

—MICHAEL HOFMANN

New Brunswick

October 2003

THE STALIN FRONT

PROLOGUE

The Lance-Corporal couldn’t turn in his grave, because he didn’t have one. Some three versts from Podrova, forty versts south of Leningrad, he had been caught in a salvo of rockets, been thrown up in the air, and with severed hands and head dangling, been impaled on the skeletal branches of what once had been a tree.

The NCO, who was writhing on the ground with a piece of shrapnel in his belly, had no idea what was keeping his machine-gunner. It didn’t occur to him to look up. He had his hands full with himself.

The two remaining members of the unit ran off, without bothering about their NCO. If someone had later told them they should have made an effort to fetch the Lance-Corporal down from his tree, they would quite rightly have said he had a screw loose. The Lance-Corporal was already dead, thank God. Half an hour later, when the crippled tree trunk was taken off an inch or two above the ground by a burst of machine-gun fire, his wrecked body came down anyway. In the intervening time, he had also lost a foot. The frayed sleeves of his tunic were oily with blood. By the time he hit the ground, he was just half a man.

With the machine gun out of action, the log-road lay open before Lieutenant Vyacheslav Dotoyev’s shock troops. He motioned to the rumbling tank in front of what was left of his little bunch of art students from the Stalin Academy. The chains rattled. Another minute, and what was left of the Lance-Corporal was rolled flat. The budding artists didn’t even get a chance to go through his pockets.

Once the tank-tracks had rolled out the Lance-Corporal, a fighter plane loosed off its explosive cannonfire into the mass of shredded uniform, flesh and blood.

After that, the Lance-Corporal was left in peace.

For four weeks, he gave off a sweetish smell. Till only his bones were left on the grassy forest floor. He never got a grave. A couple of days after he lost his hands, his Captain set his name to a report. The Sergeant had drawn it up.

Quite a few of these reports had come in. The Captain on that day signed seven, but the Sergeant showed no sign of flagging. The reports were submitted in order of rank. The report on the decease of the Lance-Corporal was signed after the report on the NCO. In this way, the Sergeant kept a little order. These and other such refinements meant he was indispensable at headquarters. He didn’t realize he was simultaneously taking orders from fate. Only the Lance-Corporal would have been in a position to confirm that the beginning of the salvo had hit his NCO, and that it wasn’t for another second or two that he himself was hurled into the air. But the Lance-Corporal was in no condition to give a report. He didn’t even have a hand with which to salute. And so there was a touch of providence in the way everything was taken care of.

When the Captain signed the reports now, he no longer bothered to ask the Sergeant whether such and such a man was married or not, or whether his mother was still alive. By the time his own turn came, no one would bother either. Asking such a question didn’t exactly do him any good. It wasn’t that he cared. He wanted to live, they all wanted to live. He had reached the conclusion that it was better just to stay alive, and forget about playing the hero.

<

br /> When he got the chance – which happened most nights – he would try to make a deal with God, after ten years in which he hadn’t given Him a thought. Depending on the intensity of the bombardment that was coming down on the shelter, he would offer Him a hand, or a foot. In return for letting him live. When the Russians took the log-road, he offered God both his feet. It was only his eyes that he wouldn’t give up. He didn’t mention them in his prayers.

So far, however, God hadn’t shown much interest in doing a deal. Maybe it was His way of taking revenge for the ten years in which he hadn’t thought about Him? It was a difficult thing for the Captain to renew their relationship after such a long time. To begin a conversation with God as if he were still a deputy headmaster seemed ridiculous under the present circumstances. Better, then, to step before Him as a company commander. But that made it harder to dicker over his personal fate. The Captain left his request till the very end of his prayer. His only way of making its importance clear was by declaring his readiness to take certain sacrifices upon himself. It wasn’t until later that it occurred to him to implore God humbly for his life. Later, when he was forced to stay in his shelter and wait while a Russian outside decided whether or not to toss in a hand-grenade. After ten years as a deputy headmaster, he couldn’t know that you didn’t need God for the fulfilment of such a prayer.

A Corporal, who hadn’t given God a thought, had scratched at the soil with his bare hands for so long that the skin on his fingertips hung down in shreds, and then he had calmly sat and watched as flies and mosquitoes had settled on the raw flesh and introduced into his organism certain substances that he required for the fulfilment of his plan. A few days later, with swollen hands, a high temperature, and various other ambiguous symptoms, he had been taken to the dressing-station. That Corporal had taken the easy way. He hadn’t tormented himself with any relationship to God. It was twenty years since he had last seen inside a church. Later on, he felt no desire to, and God didn’t cross his path a second time.

The Stalin Front

The Stalin Front